Karen Baldner, an associate faculty member of printmaking, is committed to helping her students develop their ideas and create something that genuinely represents them while providing guidance and feedback. Recently awarded a 2023 Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Teaching, she has gone above and beyond to provide students with opportunities and an environment to succeed.

Baldner believes everyone has a distinct point of view. She encourages all her students to explore by taking risks and trying new things while also developing their technical skills in book arts, papermaking, and letterpress — giving them the solid foundation they need for success.

We asked Karen about her teaching style and artistic work for our "Five Questions" Q&A series, in which we ask various faculty members for sage advice and insight into their creative disciplines.

HERRON: You began teaching at Herron in 1998 and continue to commute between Bloomington and Indianapolis to this day. What excites you most about being in Eskenazi Hall — and why?

KAREN BALDNER: After having taught at five different schools before walking through Herron's doors, I was amazed at the quality, dedication, and passion that my Herron colleagues put into teaching. Nowhere else did I experience such an atmosphere of commitment to high standards, which matched how I personally felt about teaching.

Initially, what kept me at Herron was how much I could learn about teaching drawing. But then, the opportunity to teach book arts was dropped into my lap. This included two courses, bookbinding and an artist books class, and the seed for developing a minor in book arts. It was the opportunity of a lifetime for me to build something I cared about at an institution I admired at a time when the book arts were still in the pioneering phase.

Herron was gracious enough to let me develop courses that belonged to the book arts vocabulary, such as papermaking and letterpress, and accommodated a space dedicated to the book arts in Eskenazi Hall when the school moved. A dedicated book arts space was the first stamp of approval for building the book arts minor, which is thriving today after 11 years of existence. Through the years, the book arts room has developed an atmosphere of its own, the composite of passion for making books by many hands and creative forces. Stepping into Eskenazi Hall every morning fills me with gratitude and excitement for being part of Herron's extraordinary community and its continual growth and amazing history.

HERRON: Both your colleagues and students have described you as an "exceptional teacher" who inspires artistic growth and experimentation. How would you describe your teaching style?

BALDNER: Teaching is humbling to me. There is so much to learn, and sometimes I receive more than I give to students. I see my classroom as a learning community (which includes myself), an inspirational environment in which each participant is guided to discover their personal and creative strengths. Communal teaching and learning extend from skill building through exploration to the ideation process. It is a laboratory-style approach inspired by the age-old traditions of shared papermaking, printing, and bookmaking shops in which artisans worked with each other, putting hands and minds together to develop ideas.

As students' skills grow within this kind of environment, they begin guiding each other and learn to use each other as resources. This becomes especially exciting when students from different departments at Herron, or disciplines from across campus, start working together. Communal learning produces a sense of shared pride in accomplishments and a sense of ownership of skills and knowledge, creating cohesiveness and shaping a classroom culture.

To me, this kind of culture is fed by my own love for teaching and my engagement with the media I teach as a practicing book artist. I see my role as providing structure, vision, inspiration, and guidance on group and individual levels. I make it my objective to bring a successful experience within students' reach, encouraging students to work within their personal range of strengths. I help them set realistic goals and timelines, allow ample room to explore and play, filter out excess information, prioritize intentions, and ultimately experience satisfaction and pride through closure.

I recognize that processes are as important as the goals they try to achieve because they can change them. Pursuing an idea, falling on your nose with it, and making time to follow a revised direction is part of the creative process of building personal content. I have learned that this exploration process is often at the heart of real growth for students. It is also important for me as the teacher to know when to step aside and let the growth process unfold on its own.

HERRON: You teach book arts, letterpress, and papermaking in Herron's printmaking program. Printmaking as an art form dates back to the Han Dynasty China, between 206 B.C. and 220 A.D., and letterpress is a nearly 600-year-old process. What draws you to these art forms, and how do you see students using them today?

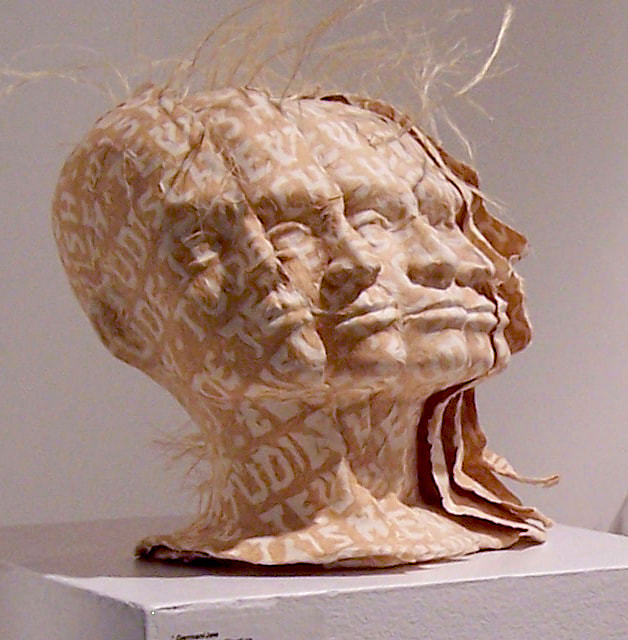

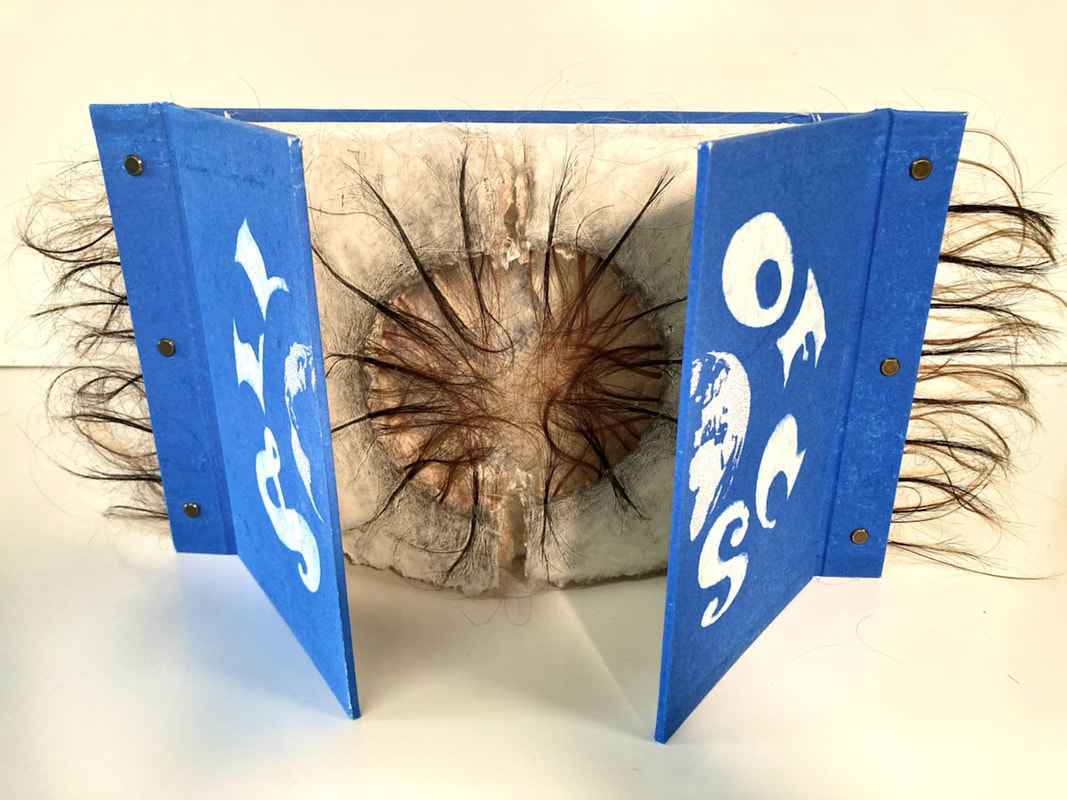

BALDNER: It is a privilege that, as book artists, we can insert ourselves creatively into age-old technologies that are so loaded with human history. Paper, printing, and books were at the crux of times when societies made big leaps in growth toward becoming more democratic in their information distribution. Today, we are experiencing another big leap in which the digital world is replacing books and printed copy. This makes books available to be inhabited with new meaning, which includes how they are made, what they are made of, and their use as creative vessels in their own right.

I find the structure of books tremendously expressive — their compactness and qualities of containment, their inter-dimensionality, and their sequential unfolding of worlds, images, text, and narratives. I come from a family of publishers, and that, added to the already rich historical significance of books, has become a calling for carrying a tradition into a new historical context. Because of their history, books draw a certain respect for me, and I try to fold this respect into the narratives of my artist books.

This nod to history is also part of my teaching. I bring binding styles, papermaking, and printing processes to students in their historical context and tailor assignments to the purpose of technologies. Students are acutely receptive to being tied into a larger historical arc. They are also fascinated by the analog world that surrounds the book arts. The digital age is beginning to remove us from physically engaging with our world, and book-, paper-, and printmaking technologies bring students back into engaging with their hands. There is a special pride for students in building hands-on skills, becoming proficient with tools and equipment, and putting them into personalized use. But there is also room in the book arts for creating hybrids between digital technologies and analog processes, creating exciting new expressive formats unique to both directions.